April 29, 2025 | By Rebecca Griffiths and Julie Kelleher

ASU-GSV and the affiliated AI Show featured characteristic excitement about the potential of educational technologies powered by artificial intelligence to transform education at scale. However, much of the buzz seemed to be coming from the big AI players (e.g., OpenAI, Anthropic, Google) rather than new education-specific ventures, and much attention focused on higher education. What’s going on?

What is the edtech landscape in 2025?

While K–12 has long dominated the edtech market, we saw more activity in higher education than K–12 at the AI Show. This reversal likely reflects greater autonomy of faculty and institutions to experiment with novel technologies, as well as prevalent concerns about data privacy in K–12. Higher education is also encountering AI disruption from two directions that make it harder to ignore – meteoric uptake by students and potential dislocation of employment pathways.

It is unclear how many of the new entrants in higher education have staying power. We noted that most new higher education entrants are “1:1 point solutions” for faculty to license and use individually (versus department, school, or college implementation). For example, we know of a couple dozen course-builder startups that popped up over the past year. Many of these startups feature “wrappers” or product layers (such as friendly interfaces designed to serve a specific function or use case) on base AI models and describe their products as “AI-native,” “AI-first,” or “AI-powered” products.

For one, much of the power of these products comes from underlying base models (such as ChatGPT). Users may feel they get much of the same benefit from customizing their own GPT, Claude Project, or other AI tool they’ve grown accustomed to using. The product layers are relatively easy to replicate and could be absorbed by the major AI companies, as ISTE’s Joseph South noted in a recent LinkedIn post. For example, Claude recently announced a “learning mode” that aims to guide students’ reasoning process rather than provide answers, likely undermining the continued relevance of some AI education projects. Anthropic is also working with Instructure to embed AI into Canvas LMS, potentially replicating the functionality of course-building tools.

Another limitation of the startup offerings is that they are product-centric (versus learner- or instructor-centric), meaning they require users to learn a new interface independent from existing systems such as the learning management system and other course tools. Some repackage an existing AI tool with the label of “for education” without tailoring the user experience for education-specific use cases.

Institution-wide implementations of AI in U.S. higher education so far appear limited to the major AI companies, such as OpenAI across the California State University (CSU) system and Northeastern University’s agreement with Anthropic. These arrangements primarily provide students and faculty with access to premium versions of existing AI tools. CSU’s implementation uses ChatGPT Edu, which OpenAI describes as having enterprise-level security and controls and greater affordability for educational institutions.

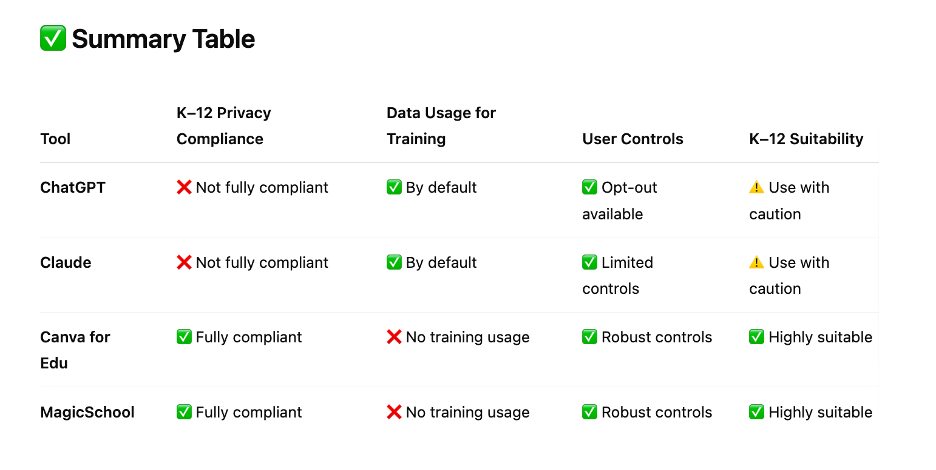

Meanwhile, the K–12 marketplace for organizational implementations of AI-centered tools is evolving more slowly, due in part to concerns about data privacy. Decision criteria for district and school leaders to adopt edtech and tools with AI features will likely include the company’s compliance with existing data privacy laws, and in some cases a willingness to sign a data privacy agreement. These requirements may introduce challenges for startups built on base AI models that do not meet the data privacy prerequisites of a K–-12 school or district.

The table below shows how some tech companies address data security, according to a query of ChatGPT. Note that when data are used for training, that means user data are being shared with the company providing the base model.

Output from ChatGPT prompt on 4/18/25: Provide an overview of data privacy settings for K–12 across ChatGPT, Claude by Anthropic, Canva for Education, and MagicSchool

At both the AI Show and ASU-GSV, we were generally struck less by an explosion of cool, new AI-powered tools and more by nuanced discussions of how AI tools should support teaching and learning, and implications for workforce education. Across sessions, speakers emphasized the importance of centering learners and pedagogy in the design and use of technologies. Personalized learning systems have a place, but the most exciting vision of education is not each student working individually online toward skill mastery. Teachers should be supported to leverage technology in service of their pedagogical goals and where they want to take their classrooms. For novice teachers, AI “game changers” are tools that help them create high-impact learning activities in response to real-time needs.

We were also impressed by efforts of some districts to thoughtfully and carefully implement AI tools to achieve specific goals. For example, Poway Unified School District (California) focused on Digital Agency & AI Literacy for Ethical and Creative Use through the lens of an important question: How can educators help students use AI safely, ethically, and responsibly AND innovate with creativity? The district’s AI in PUSD Framework focuses on the fundamentals first: AI literacy, data privacy and security, and digital citizenship and ethical use. Building on those fundamentals, the top two tiers in the framework introduce AI in the classroom and support continuous learning and adaptation, serving as an example of scaffolded teacher and student-centric AI adoption.

What are the implications for developers?

We work with many researchers developing innovative, evidence-based applications to improve student learning and achievement. For those in academia or nonprofit organizations, ruthless market competition is unfamiliar terrain. We offer a few thoughts about what types of ventures, commercial or mission-driven, could have promise.

The most promising developments are thoughtful implementation strategies that prioritize fundamentals: privacy compliance, support for good pedagogy, and human-centered design. While we’re witnessing a proliferation of tools, particularly in higher education, true scaling requires shifting from isolated point solutions to institution-level implementation frameworks that deliver consistency, accountability, and measurable outcomes. As we move forward, the focus must shift from technology-first to learning-first approaches that leverage AI not as stand-alone tools but as integrated components of comprehensive education ecosystems.

Tags: Artificial intelligence Education technology Innovation