October 24, 2024 | By Keena P. Walters

Research suggests that the use of evidence-based and other high-quality instructional materials can offer significant improvements to learning outcomes.1 But how do evidence-based educational products make it into the hands of students and teachers?

It often starts with a district or school procurement process. This process includes discovering, evaluating, selecting, acquiring, and piloting educational products. As defined in the LEARN to Scale Toolkit, an educational product is an intervention, program, or solution designed to meet a need in an educational setting. Examples include curricular materials, educational technology, and professional development.

Product procurement involves discovering, evaluating, selecting, acquiring, and piloting educational product.

Examples:

Discovering – district leader attends an Ed Tech conference and finds useful reading software

Evaluating – a principal asks several teachers to try out a supplemental math book in their class

Selecting – a curriculum director picks a reading tool from a vetted list

Acquiring – a district has principals and teachers meet with the vendor or a new product to discuss how to implement the product

Importantly, the quality and relevance of educational products used in schools are influenced by those involved in the procurement process. However, until recently, we didn’t have much data on the involvement of different education community members in the procurement process across the United States. So, the LEARN Network set out to study how educational products are procured and who is involved.

The study had three main components:

- Nationally representative surveys of 1,036 principals in K–12 public schools and 208 school district leaders, administered through RAND’s American Educator Panels

- Interviews with 19 education leaders at schools, districts, and state agencies serving students from diverse educational contexts and populations

- Focus groups with 9 teachers and 11 caregivers/parents

We weighted the analytic survey samples so that our estimates would reflect the national population of public schools and districts in the United States.

We found that teachers and school and district leaders are extensively involved in procuring educational products, while other key members of the education community (students, caregivers/parents, and community members) are less involved. Below, we discuss the details of our findings and some questions that school leaders can consider to include the unheard voices in the procurement process.

Whose voices are heard in the procurement process?

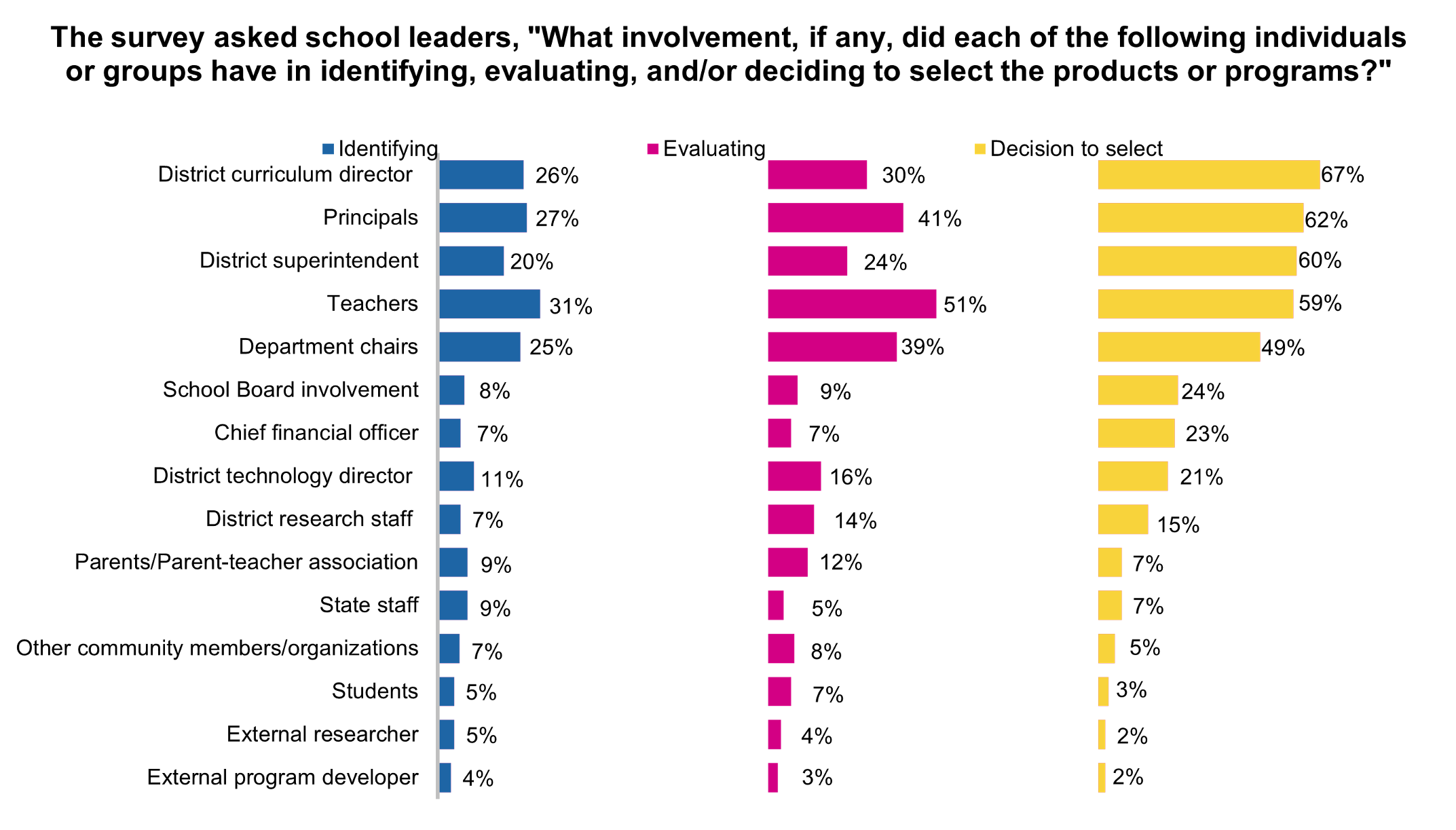

Many voices and recommendations are heard in the stages of procurement. On the surveys, school leaders often reported that teachers are most involved in identifying (31%) and evaluating (51%) products, which makes sense considering that teachers are the ones implementing the products. Additionally, around two thirds of school leaders reported that district curriculum directors (67%), principals (62%), and superintendents (60%) are most involved in selecting products. This, too, is understandable given that school leaders typically oversee the budget.

Note: This figure shows the weighted percentage of respondents who indicated that each individual or group was involved in identifying, evaluating, or selecting the products. The response options also included “not involved / not applicable” and “I don’t know.” If respondents chose one of these options, their responses are not shown.

Whose voices are not heard in the procurement process?

While our findings around those who are most involved in procurement were expected, we were surprised to discover that the voices of students, community members, and caregivers/parents are largely left out of the procurement process.

Survey responses from school leaders suggest that students are unheard and uninvolved in the procurement process. According to school leaders, students are involved in identifying products in just 4% of schools/districts, evaluating products in just 7% of schools/districts, and selecting products in just 3% of schools/districts. Community member involvement is slightly higher in identifying (7%), evaluating (8%), and selecting (5%) products, according to school leaders, but these percentages are still low.

Finally, school leaders reported that caregiver/parent involvement in procurement is similarly low for identifying (9%), evaluating (12%), and selecting (7%) educational products. Even though caregivers/parents are slightly more involved than other community members according to the survey results, most caregivers/parents in our focus groups shared that they were not involved in the procurement process or invited to participate in the identification, evaluation, or selection of products at their children’s schools. Only one caregiver said they had been involved in procuring a product for their child’s school, and that was for a product being purchased by the parent-teacher association.

Why listen?

Many people other than teachers and school leaders have a stake in the quality, relevance, and use of educational products. Students, caregivers/parents, and community members are invested in and impacted by educational products, both in and out of the classroom.

At home, caregivers/parents work closely with students to support their learning and may use products shared by teachers (e.g., curricular resources or educational apps), so they can offer unique insights. For instance, in an interview a caregiver shared that she has privacy concerns with various the educational technology products her child’s school because those products collect student data. This feedback regarding the use of a new product could be beneficial to school leaders during the evaluation or pilot of the product. Students, community members, and caregivers know and understand their own backgrounds, environments, and experiences the best, and their input can help leaders adequately meet students’ educational needs through procuring relevant products for schools and districts.

Further, most interviewees described schools and districts as having diverse socioeconomic, linguistic, racial/ethnic, and migrant/non-migrant student populations, with diverse student learning needs and gender identities/sexual orientations. On the surveys, school leaders cited a lack of research relevant to the school and district context (e.g., population) as the fourth largest barrier in the procurement process. Students, caregivers/parents, and community members can provide valuable contextual information to help leaders bridge this evidence gap.

Let’s hear it!

It’s valuable to have individuals representing multiple perspectives involved in the procurement process to share and consider student, caregiver/parent, and local community needs. School leaders who want to gather input and hear what students, caregivers/parents, and community members have to say in the procurement of educational products can consider these questions:

|

|

|

Note: Before conducting surveys or focus groups, consult your district’s research and data collection policies.

Tags: Education technology Educators and systems leaders Evidence-based Policymakers Procurement